How to compile PHP from Source

Knowing how to compile PHP will open one of the few doors necessary for contributing to the PHP language. Once you get familiar with this it will be much easier for you to contribute in many ways such as running tests and uploading reports, writing new tests by yourself and bug reporting/fixing.

I write this short guide as an effort inspired by Joe’s post on the existing Bus Factor present in the language which, in my opinion, is very alarmist but necessary. Given my limited time between working, writing posts, maintaining my projects AND contributing with PHP source it just makes more sense to me to multiply the knowledge on PHP’s source instead of trying to decrease the bus factor by one (myself).

I’ll certainly post more things about the php core, but if you have a purely PHP background and would like to get more involved without waiting for my posts (which is the correct way), I know that Nuno Maduro will be talking about PHP Internals focused on PHP engineers soon so keep an eye.

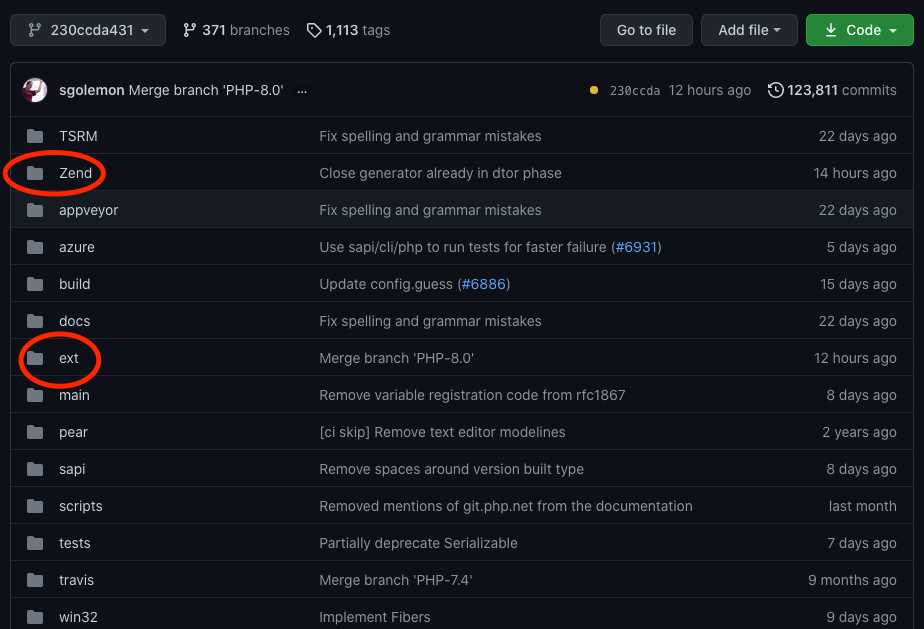

We’ll be visiting the php’s source code available on Github. Click here to visit it.

PHP’s source is split between core (/Zend) and interface (/ext)

Before we start I need to give you an oversimplified explanation of PHP’s folder structure. There are the /Zend and /ext folders.

/Zend holds the Virtual Machine’s code, also known as the Zend Virtual Machine (Zend VM). It is responsible for tokenising, parsing, compiling, managing the call stack and, in general, running PHP code.

If you had no idea PHP had a Virtual Machine, please also consider reading this post that explains about the PHP engine and the Just in Time compiler, it explains how php works from PHP source, through compilation to runtime and will give you the keys to open many other doors in the future. Nothing much complicated, just have a read 😉

/ext is where the magic happens. This is a folder for extensions supported by the PHP team. Every function and class that exists in PHP comes from this folder. For example, under /ext/standard you’ll find all functions that come with standard PHP. String-related functions can be seen here.

One way of looking into the /ext/ folder is to think that every extension there is a wrapper to a C library: a portion of C code that makes available to PHP operations only possible in C.

The main reason I’m telling you about /Zend and /ext/ is that you’ll always compile /Zend when compiling PHP. But you may cherry-pick which extensions you’ll be compiling for your PHP binary. This is particularly useful for running tests and debugging.

Long story short: you can disable most extensions and opt-in to extensions you’d like to compile. You can’t opt-out from compiling /Zend.

Following this tutorial

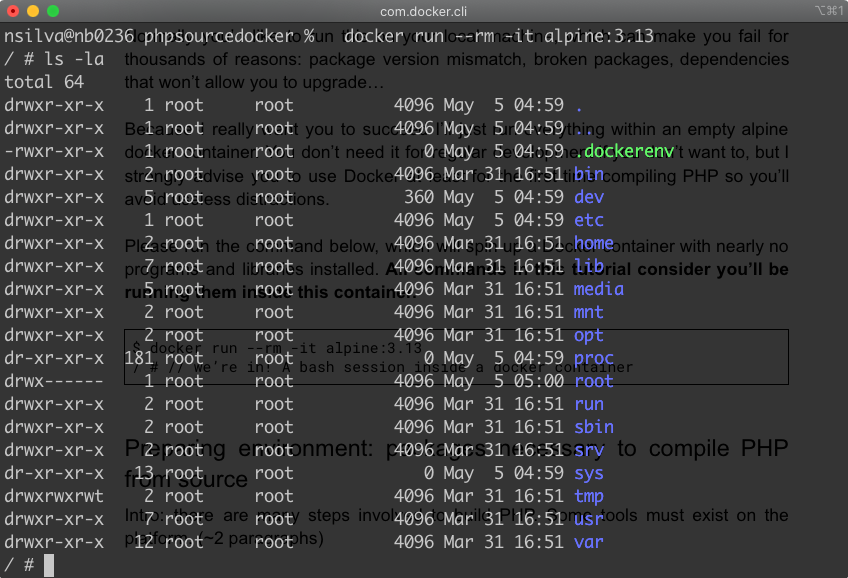

Normally you’d like to run this on your local machine, which can make you fail for thousands of reasons: package version mismatch, broken packages, dependencies that won’t allow you to upgrade…

Because I really want you to succeed I’ll just run everything within an empty alpine docker container. You don’t need it for regular development if you don’t want to, but I strongly advise you to use Docker at least for the first time you compile PHP so you’ll avoid useless distractions.

Please run the command below. It will spin up a Docker container with nearly no programs and libraries installed. All commands in this tutorial consider you’ll be running them inside this container.

$ docker run --rm -it alpine:3.13

/ # // we're in! A bash session inside a docker container

Preparing environment: packages necessary to compile PHP from source

PHP’s source code has many dependencies. Some of them are related to C compiling, others are about tokenising and parsing, others are accessories depending on which extensions you choose.

The requirements listed here are the bare-minimum necessary to a raw PHP set-up, with no extensions. When adding new extensions, you’ll need to add more dependencies to this list.

Below I’ll give you a short introduction on each dependency in the hope it will make things slightly clearer to you and potentially get you curious about them.

gcc

GCC (GNU C Compiler) is an open source C compiler, widely used by most C projects out there. It transforms C code into binary objects your computer can execute.

libc-dev

The C language is very raw and doesn’t provide tools for handling strings, files, network and so on. Thus the libc comes to the rescue: it is a set of functions that will make C development much saner: you probably have seen stdlib.h, stdio.h or string.h somewhere, they’re all from libc.

autoconf

Autoconf is a build configuration generator tool. This program is executed when you run the buildconf step.

bison

Bison is a parser generator. Whenever you find a file with extension .y, you can be sure that php’s build will use Bison to transform that .y file into a .c file that knows how to parse tokens.

re2c

Re2C is a tool responsible for compiling regular expressions into very fast C lexers.

make

Make is a build automation tool, very versatile one. It reads definitions from a Makefile which tells which actions are required for a certain build step.

There are different compilation steps, here’s why

When we compile C code, normally we choose a target machine: a specific CPU architecture and a specific operating system. A binary compiled for Windows won’t easily run on Linux without some sort of emulation in place. Similarly, a 64-bit program won’t run on a 32-bit system.

Gets even more complicated when you take CPUs in consideration: each CPU may have its own way of processing opcodes, reading memory, communicating with the BUS... So gcc’s job is to, given a target CPU and target OS, transform C code into binaries specific to that CPU and target OS. Sometimes you’re compiling something on your machine to run on another device too: with different OS, different CPU and potentially different library paths.

All the above constraints make it very hard to write a single Makefile that can capture all requirements from all possible platforms and CPUs. So what PHP project does (and this is common practice for large C projects) is generate an appropriate Makefile before build.

It takes many m4 macros, generates a configure script from them and this script when executed generates a platform-specific Makefile that will compile PHP without much trouble for you.

This might seem a bit weird right now, but let’s follow the step-by-step compilation guide I wrote you here and hopefully things will become clearer.

Let’s build PHP from source

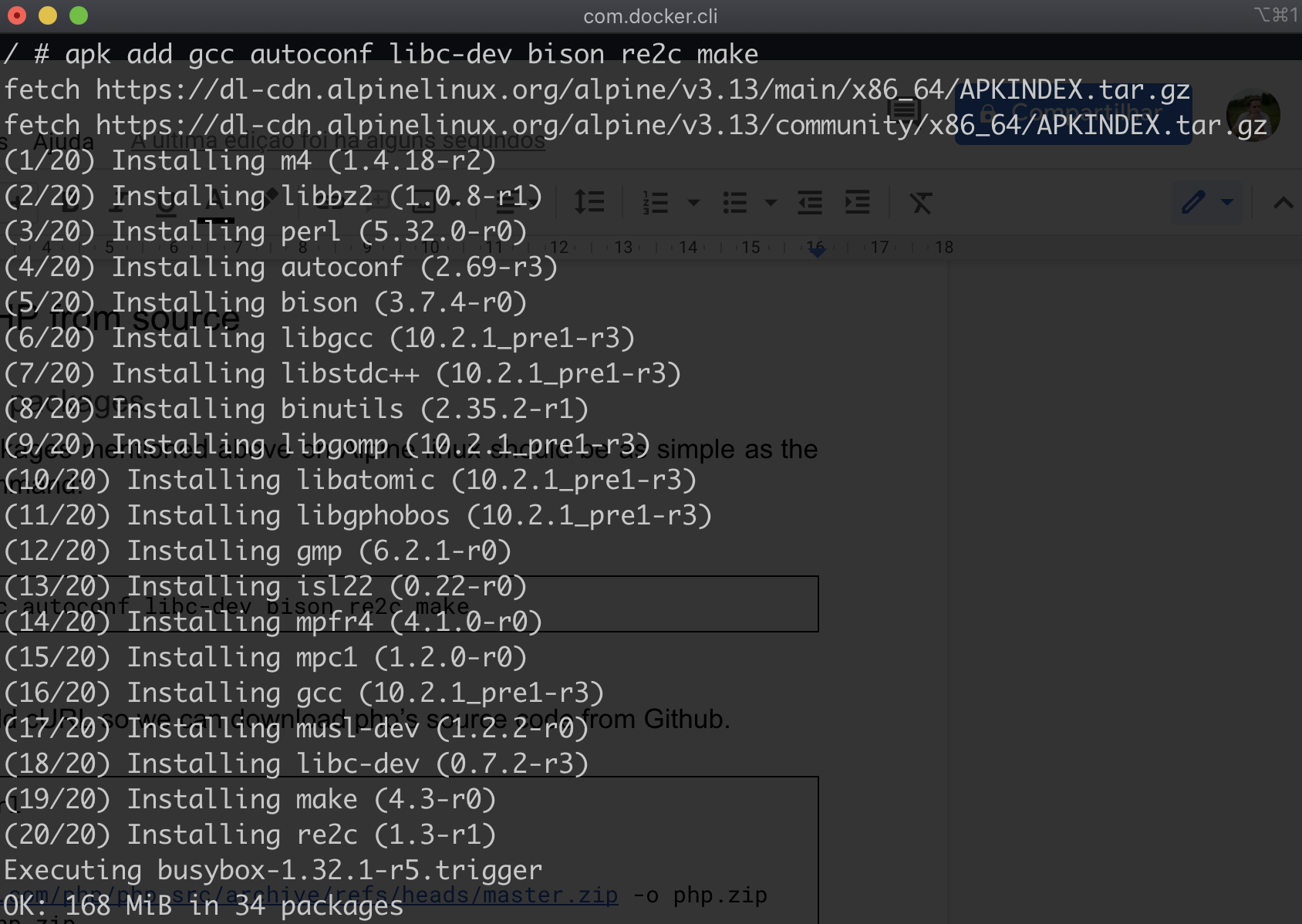

Install required packages

To install the packages mentioned above on Alpine linux should be as simple as the following apk command:

/ # apk add gcc autoconf libc-dev bison re2c make

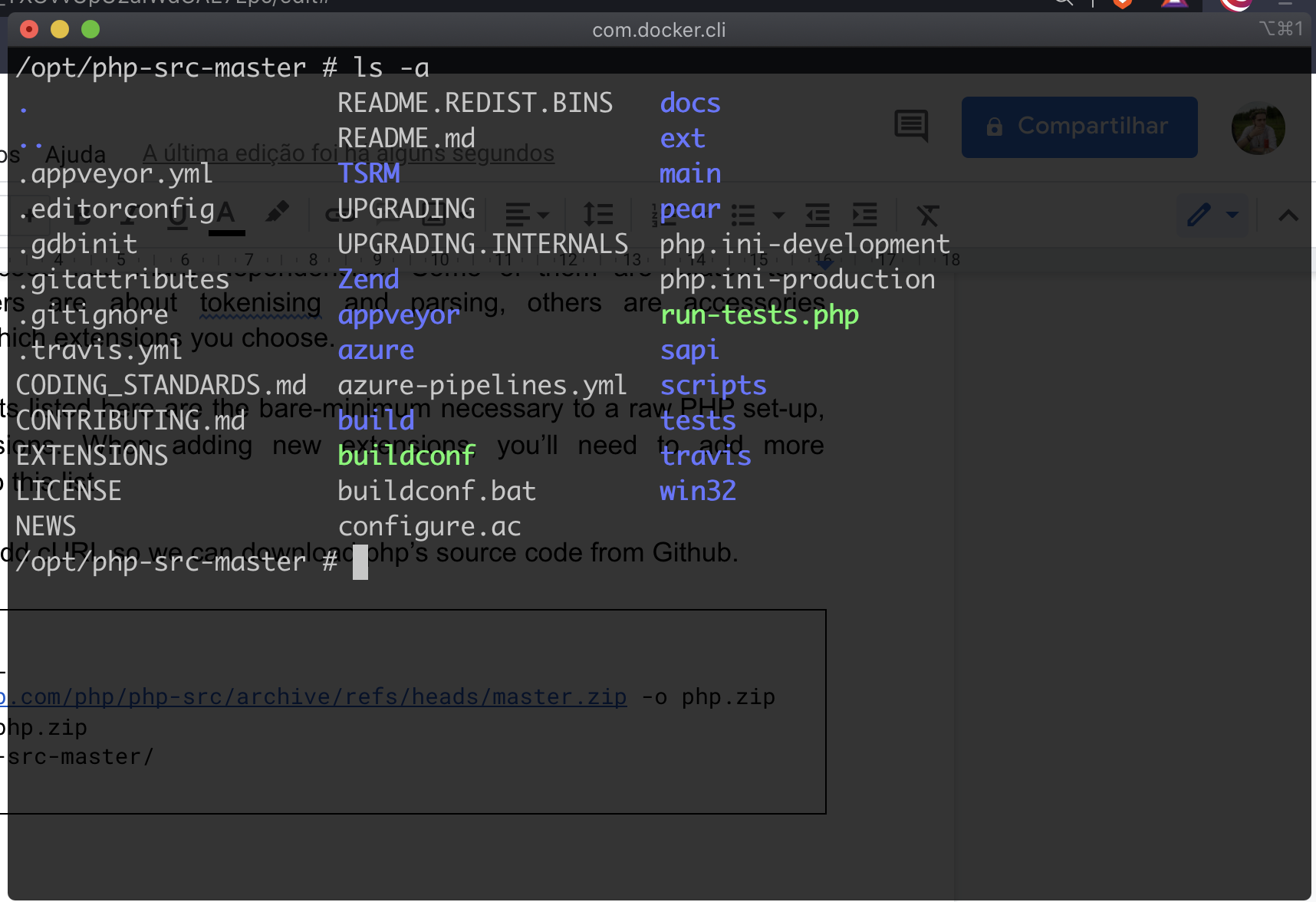

Additionally I’ll download the cURL program so we can download php’s source code from Github.

/ # apk add curl

/ # cd /opt

/opt # curl -L https://github.com/php/php-src/archive/refs/heads/master.zip -o php.zip

/opt # unzip php.zip

/opt # cd php-src-master/

/opt # ls -la

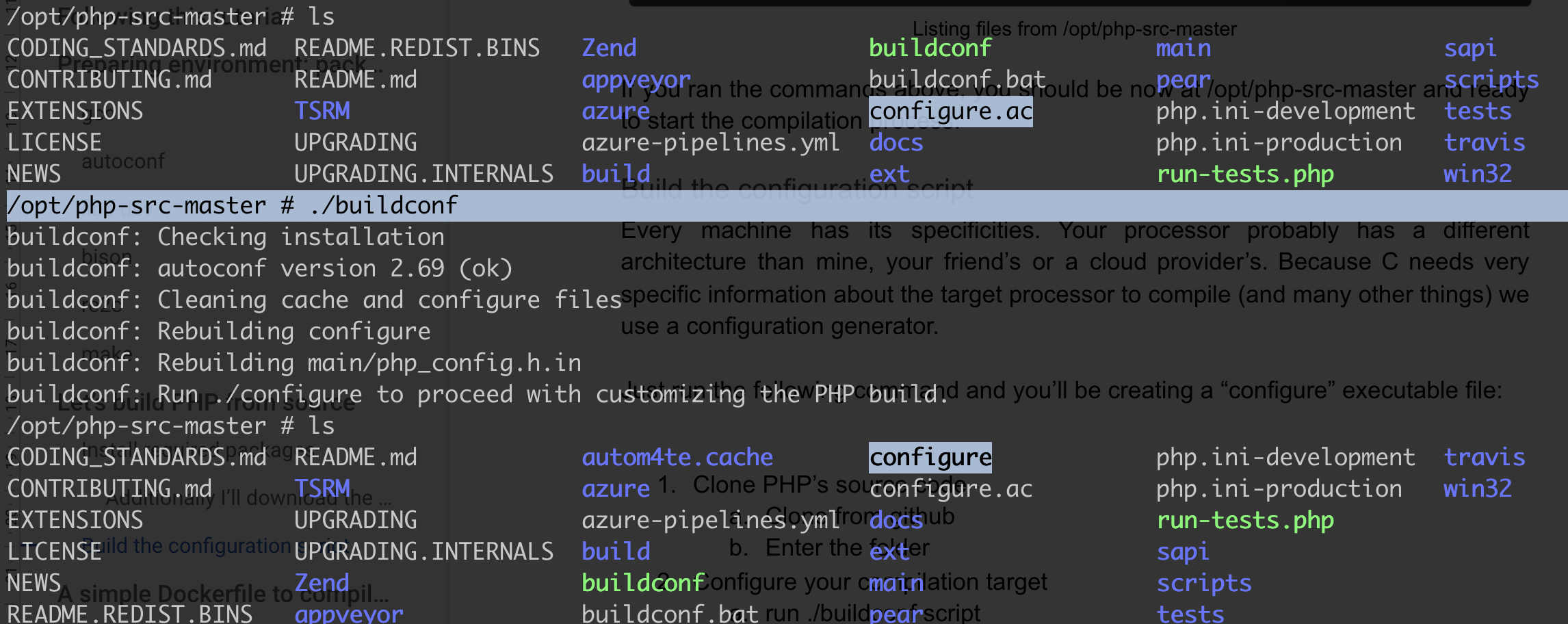

If you ran the commands above, you should be now at /opt/php-src-master and ready to start the compilation process.

Build the configuration script

Every machine has its specificities. Your processor probably has a different architecture than mine, your friend’s or a cloud provider’s. Because C needs very specific information about the target processor to compile (and many other things) we use a configuration generator.

Just run the following command and you’ll be creating a configure executable file:

3

/opt/php-src-master # ./buildconf

This step is using many .m4 macros in this project and compiling the configure file based on them, using the autoconf for this. How all of this works is out of the scope of this tutorial. Ping me if you’d like more details.

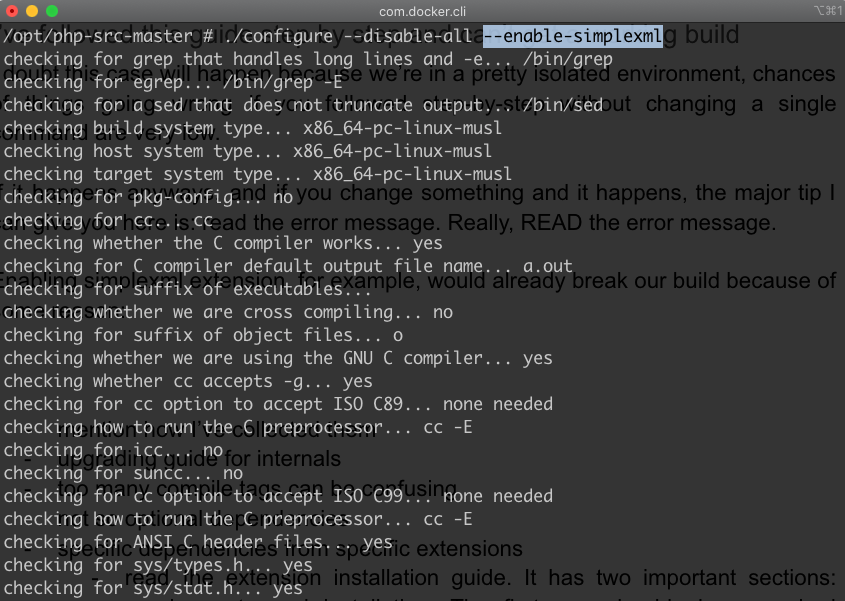

Generate the Makefile

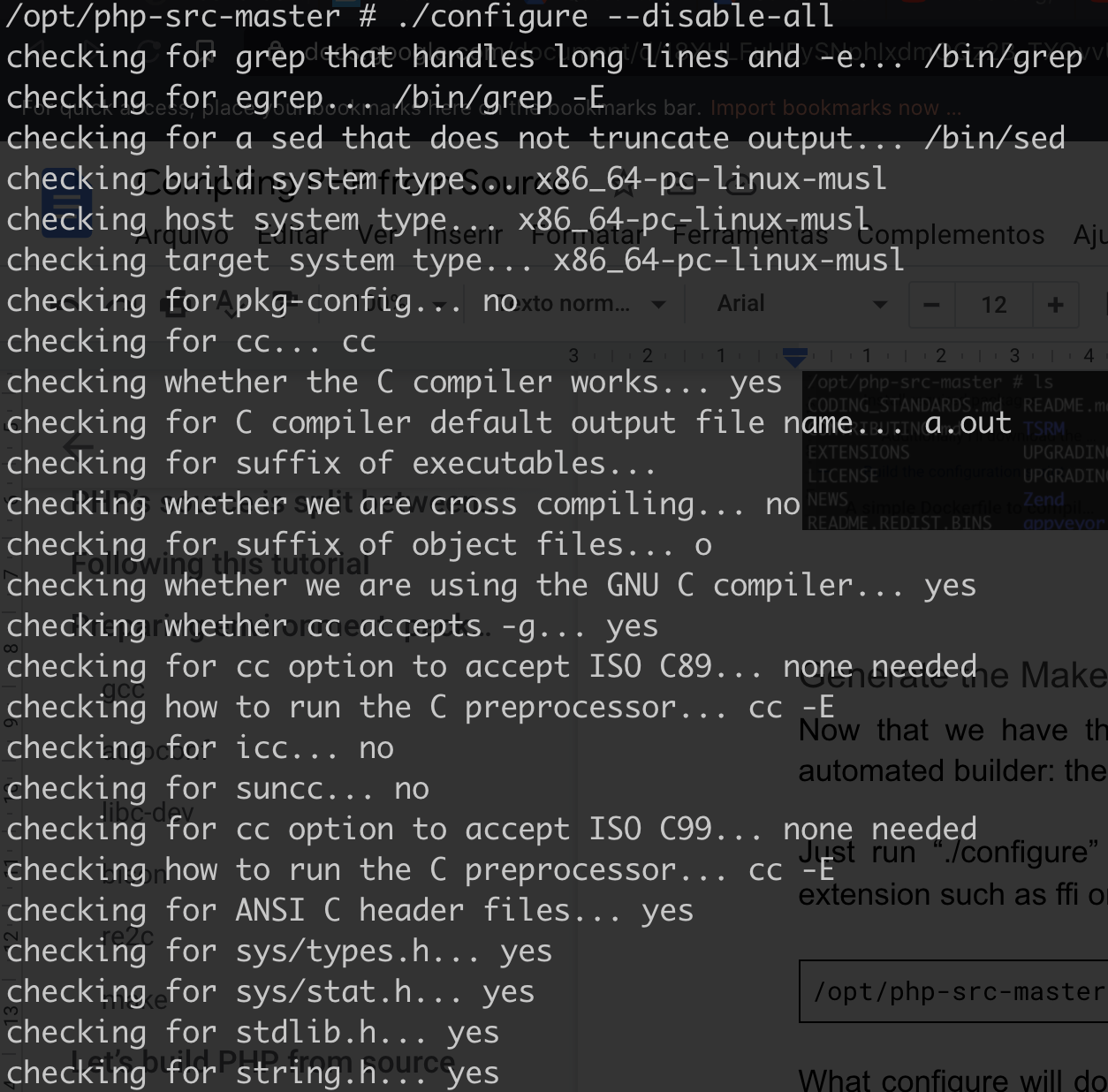

Now that we have the configure script, we may run it in order to get our automated builder: the Makefile.

Just run ./configure with the parameter --disable-all to prevent any accessory extension such as ffi or simplexml from being installed.

/opt/php-src-master # ./configure --disable-all

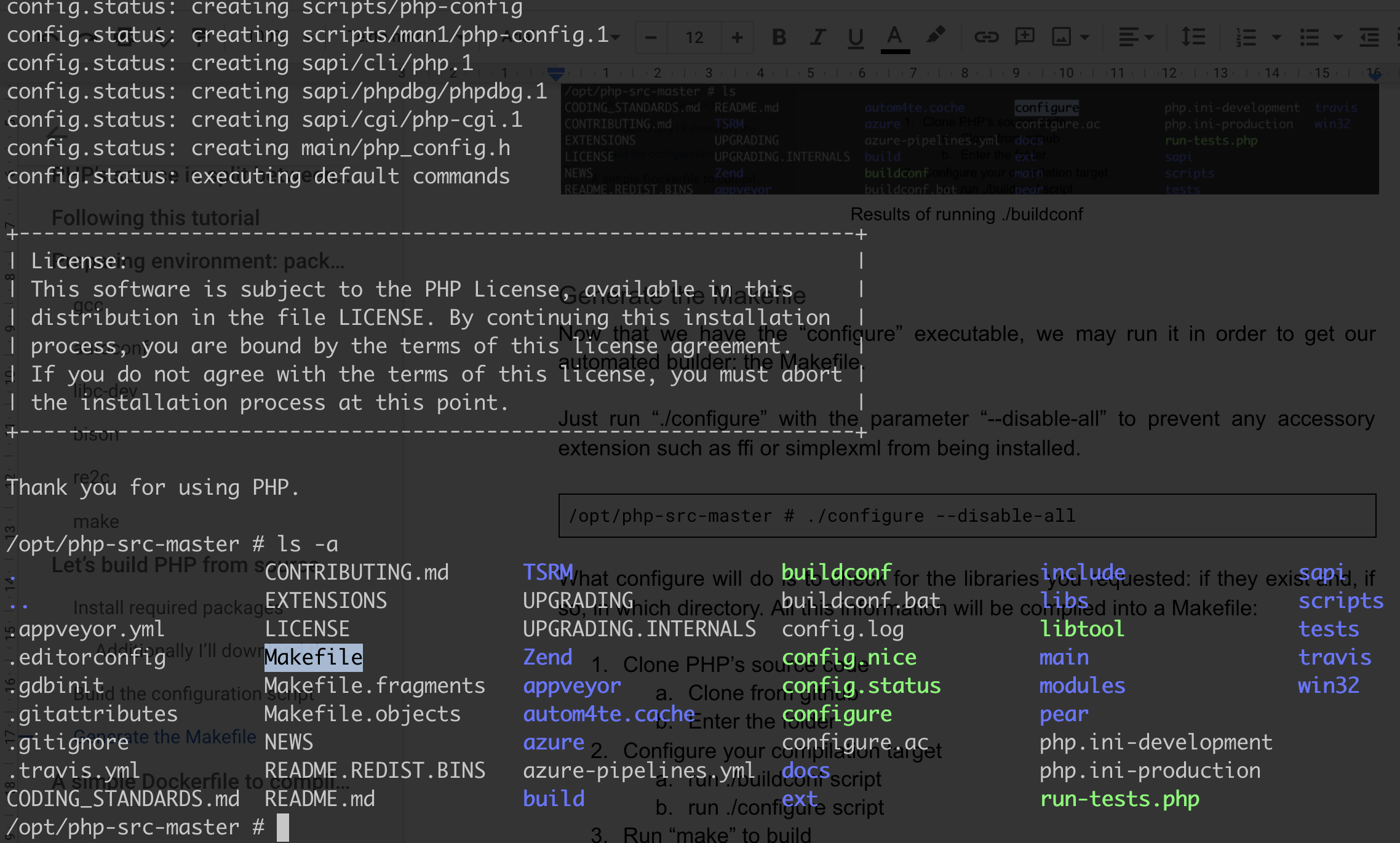

What configure will do is to check for machine architecture, tools and the libraries you requested and their directories. All this information will be compiled into a Makefile:

The created Makefile can be seen here:

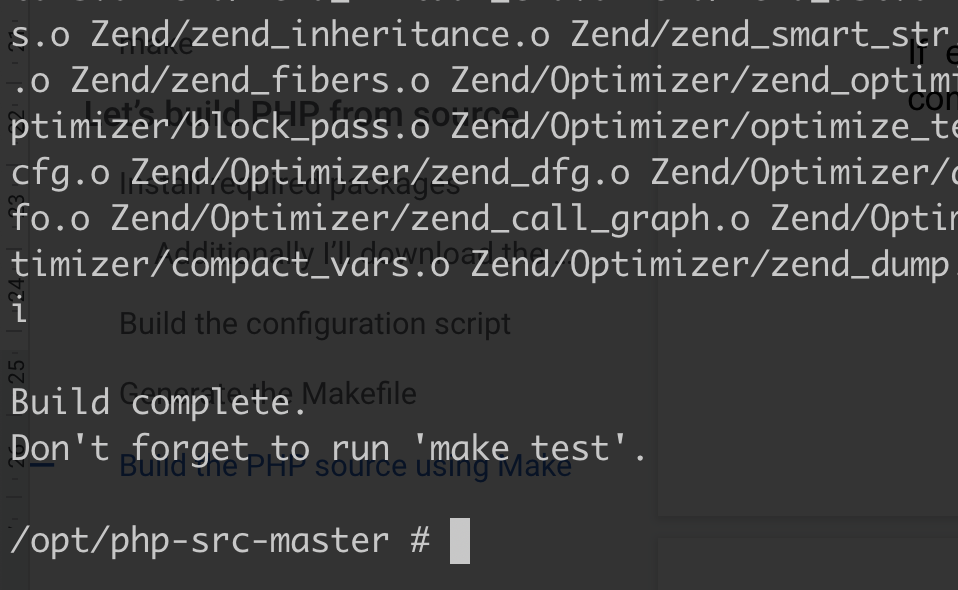

Build the PHP source using Make

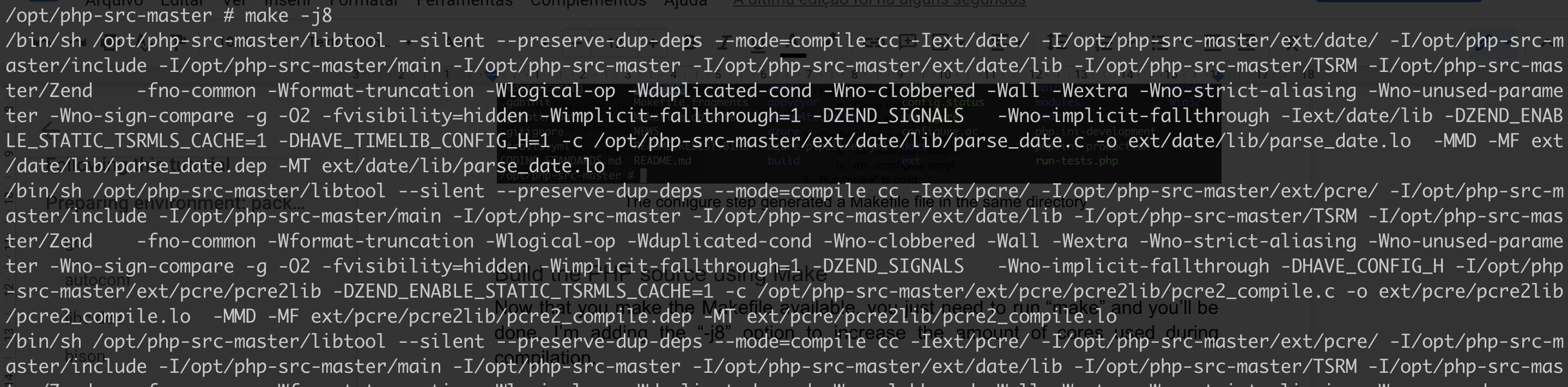

Now that you make the Makefile available, you just need to run make and you’ll be done. I’m adding the -j8 option to increase the amount of cores used during compilation.

/opt/php-src-master # make -j8

If everything went well, you should see a success screen saying that PHP was successfully built (Build complete.) and you may now run the test suite.

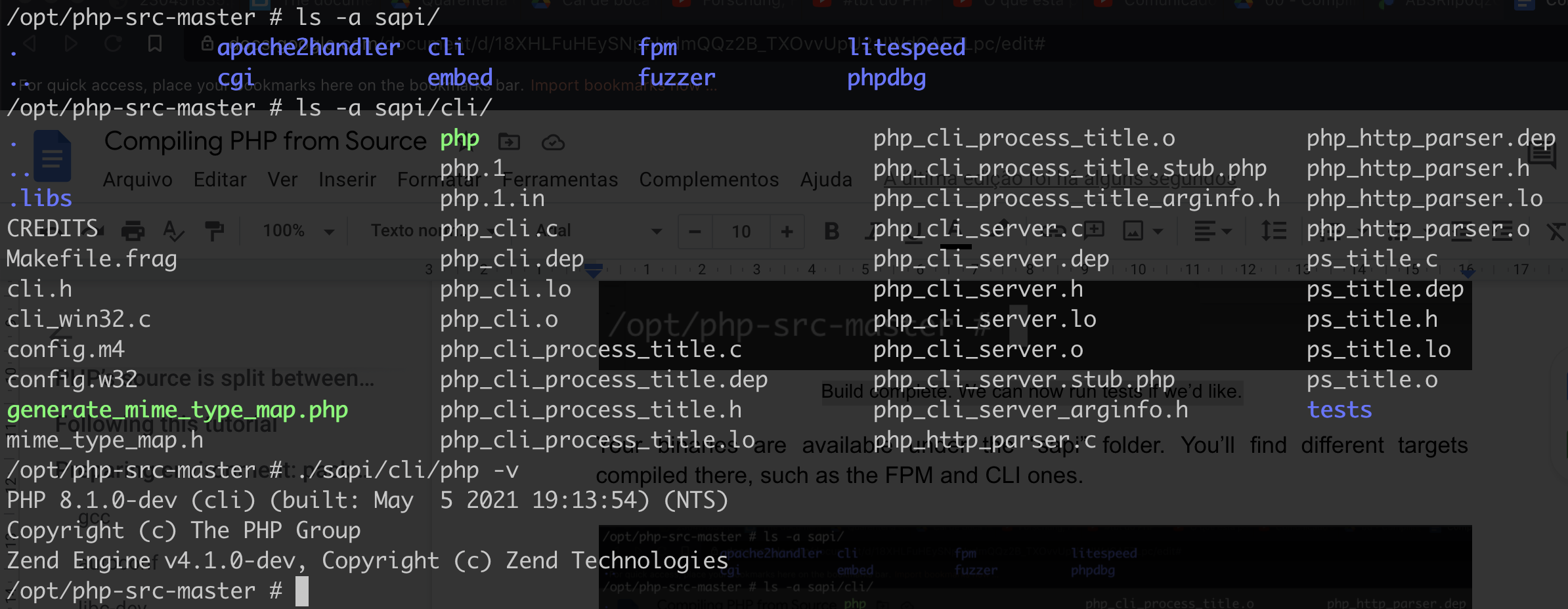

Your binaries are available under the sapi folder. You’ll find different targets compiled there, such as the FPM and CLI ones.

Be nice and run tests

Running tests won’t only assert that your compiled php works properly, but also gives you the opportunity to share results with the online community. Tests are made available here and can be used by other engineers to collect information necessary to solve issues (thanks for the hint Daniel (@geekcom2)!).

Just type in the test action from your makefile:

/opt/php-src-master # make test

If PHP failed any test, you should see a screen similar to the following:

![Screen with failed tests and the prompt “Do you want to send this report now? [Yns]” Screen with failed tests and the prompt “Do you want to send this report now? [Yns]”](/assets/images/posts/22-compiling-php-from-source-code/test-failed.png)

By choosing to send the report, you’ll be already contributing to the PHP community. Cool, right?

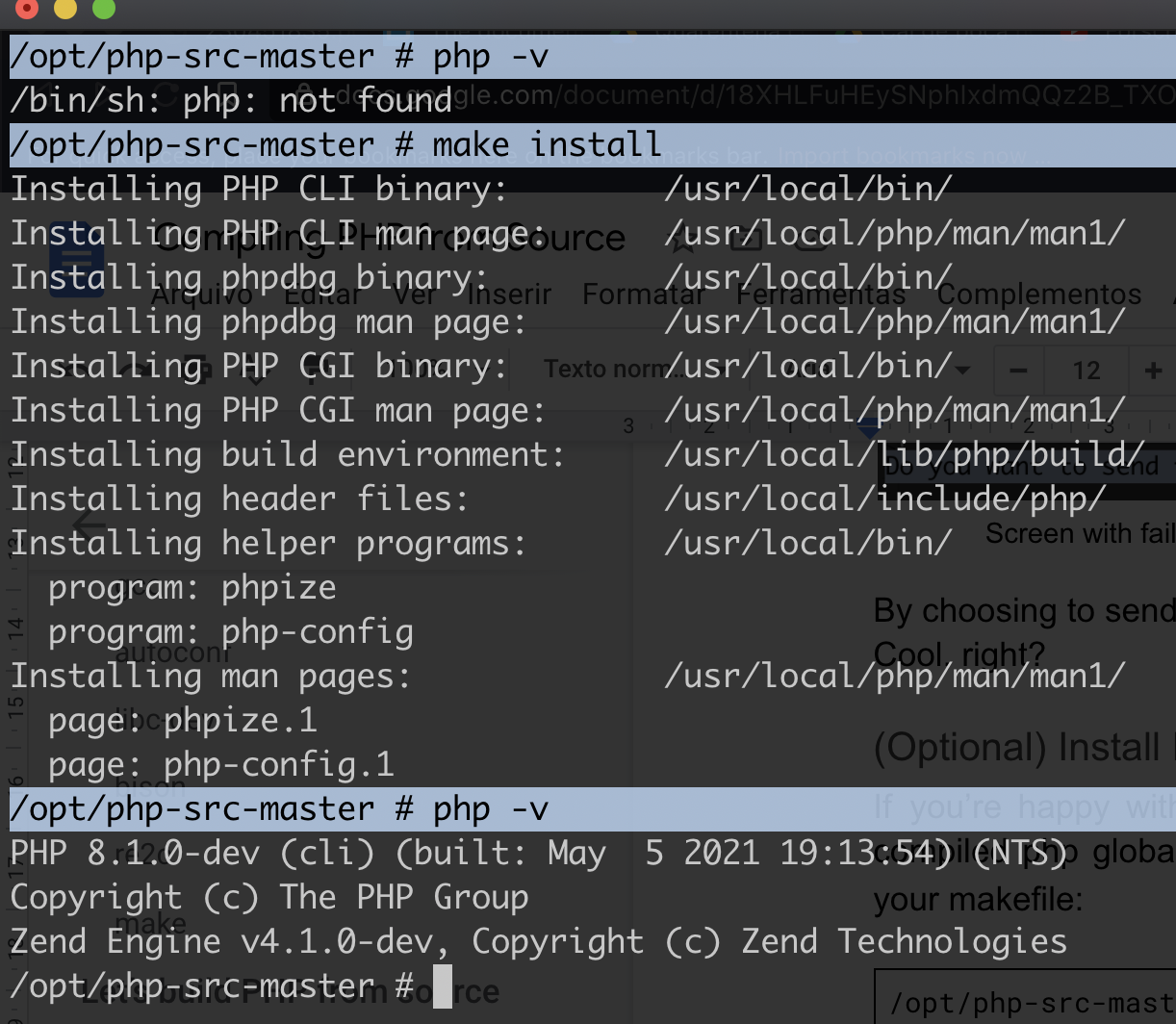

(Optional) Install PHP

If you’re happy with the compiled version you have and would like to make your compiled php globally accessible on your machine, just run the action install from your makefile:

/opt/php-src-master # make install

I don’t recommend you installing your compiled PHP unless you know very well what you’re doing. If you just need to use it for testing or playground, use aliases or add it to your PATH variable temporarily.

Common issues and mistakes

For those of you who know how to program C, this isn’t probably something that affects you directly. Because, well, you’re used with some conventions. For PHP engineers who are mere users in this C world I’ve decided to collect some hints to make the process easier.

Such hints I’ve collected by asking people on twitter and with a survey tool on this website about which issues they went through while compiling PHP. Here’s a summary of the issue and some hints of mine.

I’ve followed this guide step by step and can’t get a working build

I doubt this case will happen because we’re in a pretty isolated environment, chances of things going wrong if you followed step-by-step without changing a single command are very low.

But if it happens anyways, or if you changed something and it happened, the major tip I can give you here is: read the error message. Really, READ the error message.

Of course I don’t want to make you feel stupid, most of us ignore error messages because in PHP land we’re too used with colorful outputs highlighting which action we should take, often not really caring about the root cause of an issue. In C land, this is not common. But normally the error is the last thing you see on the screen, because a common practice is to abort right after an error occurs.

If you can’t read english well, you’ll have to guess things based on symbols. A hint for you in this case is that in C projects, if there’s an error, errors will be the last thing that happens on that program, and the program will panic (exit with an error code).

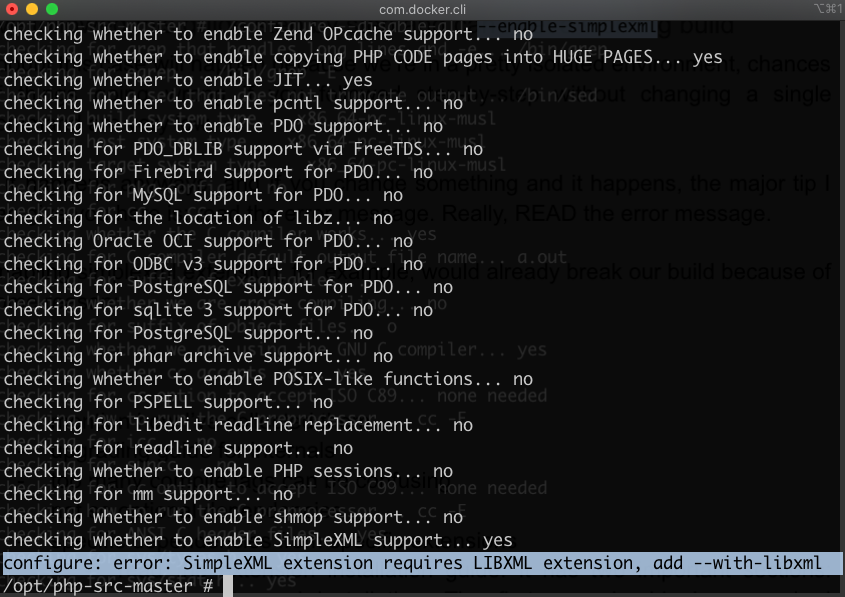

Enabling simplexml extension, for example, would already break our build for some reason:

/opt/php-src-master # ./configure --disable-all --enable-simplexml

By using the “--disable-all” flag we disabled every single optional extension, including the libxml extension that adds XML support to the core. Here’s how the error would look like in this scenario:

Notice how the message configure: error: SimpleXML extension requires LIBXML tension, add --with-libxml appeared last. That’s often how things work with C projects: one error and the whole build crashes immediately.

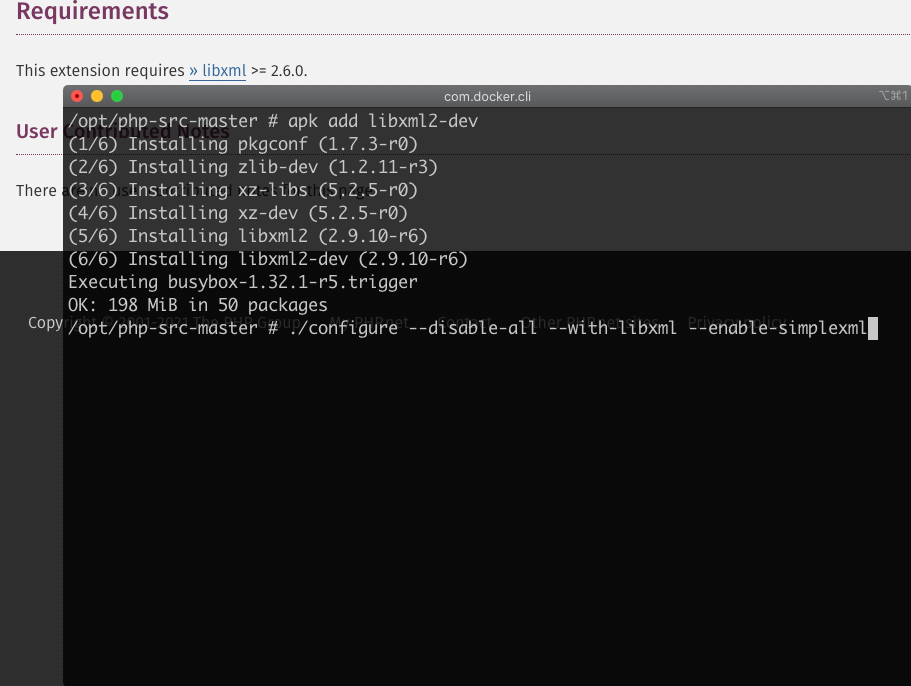

Let’s quickly visit the simplexml page on the PHP manual. There’s an entire section about xml manipulation and one of them is the SimpleXML extension page. There you’ll find the “Installation > Requirements” page.

On this page we find that "This extension requires the libxml PHP extension." even with a link. Both the configure and manual pages are aligned: we can’t install the SimpleXML extension without enabling the libxml extension. So theoretically we should just add the --with-libxml flag and everything would be solved.

But now we’re vaccinated and know that most probably we should check the requirements page before trying to build again so we avoid wasting time with avoidable issues. Let’s open the libxml extension’s manual page and check dependencies first. It says that libxml >= 2.6.0 is required. We then install it and build with libxml and simplexml extensions:

And how do I know that --with-libxml was the correct flag to use? I just read the previous error message: “configure: error: SimpleXML extension requires LIBXML tension, add --with-libxml”.

I can’t simply guess which dependencies are there

This is very correct. So far I haven’t seen a single C project with a dependency manager that will automatically download things for you like Composer or NPM would do.

With C programs you normally should fulfill dependencies manually and, believe me, this can be very beneficial. For example, this common practice reduces the size of the binary being built, because many libraries and dependencies are dynamically linked when the program loads (good old DLL / .so files) instead of copying the entire

Ideally, when enabling a certain extension, you should search for its manual page. Every built-in PHP extension comes with a manual that includes an Installation page, you’ll find all library requirements there.

I still find issues even following this guide step-by-step

It can also be that this article got outdated: PHP is a very active project, things change and you need to adapt. Take the ideas of this article as a guide so you learn how C projects are structured and the logic behind them, then apply to figure out things by yourself.

Often when breaking changes are introduced they are documented in the source code via UPGRADING and UPGRADING INTERNALS files. Have a read if you’re sure you could build it before but now something is breaking. (Kudos again to Daniel (@geekcom2) for the great tip!)

How do I know which dependencies are even available

There are many compile tags available that we can pass to the configure script, but how to find all of them?

Ideally you should know which extensions you want to enable, check their installation page and you’ll find out which tags are necessary. Make sure you read the Requirements and Installation pages, they’re essential and will bring the exact compile flags you need to add.

If by any reason you can’t (or don’t want to) visit the manual pages, you can always check the code offline. After you run buildconf a configure file will be created on your php-src directory. Just run this file with the --help flag:

/opt/php-src-master # ./configure --help

The above command will output a long list of compile flags and environmental variables you can change before generating your Makefile.

What if I need to use custom libraries or don’t want to install them globally

Oftentimes you’ll find yourself in the need to use a specific library version to build PHP, but your system already has a different version and upgrading/downgrading it for your entire system sounds a bit scary. I feel you.

One option you have is to use an isolated environment with Virtual Machines or Docker, for example. But this won’t work for all use cases.

Another option is to download and manually build your target library into a different directory, such as /opt/the-library-youve-just-built. This way you can compile the library and opt for not installing it to the system, creating shared objects that aren’t globally available and won’t mess up your OS.

If you choose the manual compiled libraries option, you must hint the configure script so it knows where to look for libraries. You can do this via environmental variables. There’s even a FAQ entry about that on the official website.

/opt/php-src-master # export LDFLAGS=-L/opt/the-library-youve-just-built

/opt/php-src-master # ./configure

I managed to compile PHP but can’t find the binary

PHP will build and place binaries under the sapi/ folder. There are many different binaries there such as the fpm, cli and embed binaries, pick the one you need.

Thanks to the Community for helping me build this article

This time instead of writing and researching everything by myself I’ve decided to ask the PHP community to support me, especially with the "Common issues and mistakes" part. I’ll drop some names and twitter handles in order to recognise and thank them all.

Follow these people if you, like me, like to make PHP cry. I guarantee great content and insights:

- Diana Arnos (@dianaarnos)

- Daniel (@geekcom2)

- Leo Cavalcante (@leocavalcante)

- Marcel dos Santos (@marcelgsantos)

- Vinícius Dias (@cviniciussdias)

- Luis Machado Reis (@luismachadoreis)

- Dev Frustrado (@geckones)

- Robson Pierre (@robsonpiere)

Some contributions were direct, with clear statements. Others just propagated my voice so I could reach more people. I’m very thankful for all of you who helped me.

Also don’t forget to follow me on twitter if you like the kind of content I share and would like to see random PHP stuff on your feed: @nawarian.

What's next?

Now that you’re familiar with compiling PHP from source code, why don’t you go ahead and run the tests, maybe break them by changing C code? Have fun!

Hopefully this step will encourage you to collaborate with the PHP community closer to its core :)

See you next time.

Cheers!